On the morning that Hurricane Irene slammed into the East Coast, most of Damien Echols’s new neighbors had fled their homes, but not Echols, who stood on the balcony of his friend’s apartment in his underwear, staring out over the rooftops, letting the wind and the water wash over him. “It had been almost 20 years since I’d felt rain on my skin,” says Echols, who is living with his wife in an undisclosed city. “Before, all I could do was sit in my cell, listen to the thunder and dream about being out there.”

Echols, 36, who had spent half his life on death row in an Arkansas state prison after being convicted of a notorious triple homicide, isn’t dreaming anymore. In a stunning reversal of fortune last month, he and the two other men commonly known as the West Memphis Three-Jason Baldwin, 34, and Jessie Misskelley Jr., 36 (both of whom were serving life sentences)-were released from prison thanks to a rarely used legal tactic (see box, page 98). Under the terms of an agreement the men made with prosecutors, they could maintain their innocence, but they had to agree that enough evidence existed to find them guilty.

“Offering innocent men, who have spent 18 years in prison, the chance to go free if they’ll say they’re guilty is a cruel temptation,” admits Baldwin, who initially rejected the offer but changed his mind because he feared for Echols, whose body was giving out under the conditions and abuse he suffered on death row. “Once I realized that this could save Damien’s life, it was a no-brainer.”

For Echols, life beyond death row has been surreal. “It’s taking me a while just to learn how to walk again because I’m so used to having chains around my ankles,” he says. But, adds Echols, who hopes someday to publish the journals he wrote while in prison, “I’ve only been out for a couple of weeks, and prison already seems like a bad dream. It seems like something that happened years and years ago.”

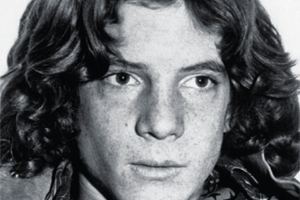

It was in May 1993 that life in his blue-collar hometown of West Memphis, Ark., was forever changed, after the savagely beaten nude bodies of three second graders, whose hands and feet were bound, were found in a drainage ditch in a wooded area near their homes. Police interviewed Echols after the murders, eventually moving on to Misskelley, a 17-year-old friend of Echols’s with an IQ of 72. Misskelley confessed after a 12-hour interrogation and implicated Echols and Baldwin. At Echols’s 1994 trial, the prosecution’s case was almost entirely circumstantial, often focusing on the precocious, long-haired defendant’s penchant for black clothing, his love of heavy-metal music and his fascination with the occult. After the convictions, HBO devoted two documentaries (a third will be released soon) to the case, which became a cause celebre for supporters, including Lord of the Rings director Peter Jackson, Johnny Depp, Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder and Natalie Maines of the Dixie Chicks.

All the while Echols was locked away alone in a 9 ft. by 12 ft. concrete cell without ever seeing the sun. As the years passed fellow death-row inmates would be led past his cell door, sometimes stopping to say farewell, on their way to the execution chamber. “Afterwards the guards would pass around a pickle jar and collect money for a beer party,” he recalls.

By necessity, Echols retreated into his own thoughts and emotions. “Sometimes I would be scared. Sometimes when I thought about my execution, I would be happy it would all just be over. Sometimes you just can’t accept it. I’d say to myself, ‘These people are not going to kill me for something I didn’t do, are they?'” His only company some nights were the rats that would creep onto his bunk and chew on his hair before he was roused for his standard 2:30 a.m. breakfast. During the day he’d run in place for hours at a time and crank out 1,200 push-ups, coating the dirty floor of his cell with sweat. But over time the stress of spending years in a tiny cell took its toll. Friends worried he would not make it. “I was getting weaker and weaker,” recalls Echols. “There were nights recently when I would lay there so sick and worn down, I thought, ‘This is it. They’re going to find my body in the morning.'” The only thing that eased the pain of his arthritic knees, hips and aching teeth-damaged, he says, from beatings by guards-was eight hours of meditation he learned from the Buddhist masters who traveled to the prison just to teach him. “That and my wife were the only things that saved my life,” he says.

His wife, Lorri Davis, a soft-spoken landscape designer from New York City who moved to Little Rock and married Echols in 1998 after watching a documentary on the case, spoke to him on the phone every day, her phone bill totaling $100,000 over the years. On Fridays she’d drive to the prison, and they’d often sit separated by a 1-in.-thick piece of Plexiglas as Davis would update him on the latest twists and turns of his case. “I only missed one Friday visit in the past 13 years,” says Davis, who quit her job so that she could spend her time trying to get her husband out of prison.

She often came with bad news, explaining efforts to get new trials failed, but there was also good news: In 2007 celebrity supporters raised enough cash for a new defense team, which was made up of more than a dozen of the nation’s top forensic scientists and attorneys.

On Aug. 9 Echols’s life changed when the state’s attorney general shocked everyone by setting up negotiations between prosecutors and defense attorneys that stretched out 10 days. “I lived in horror that at any given moment they’d come back and say, ‘We changed our minds,'” recalls Echols. “I didn’t sleep for four days. I just paced my cell. That was more stressful than all the 18 years before.”

On Aug. 18 the three were transported from their prisons to a jail in Jonesboro, Ark. The next day at a nearby courthouse, guards removed the defendants’ ankle chains and handcuffs, and a judge-after ejecting a victim’s family member for his vocal objections-set them free. “I didn’t know if it was some kind of game or what,” recalls Misskelley. “But when I came out of that courtroom and got in the car, I told my sister, ‘Go, go, go. Let’s get as far away from here as we can.’ ”

After a quick visit to pick up ID cards at a local DMV, Echols and Baldwin attended a hotel rooftop party with Vedder and Maines, then hopped a private jet provided by supporters (Echols’s first time ever on a plane) and left Arkansas, vowing never to return.

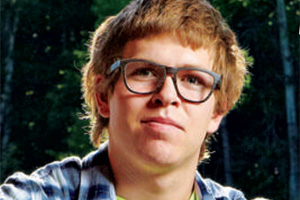

Of the trio, Echols’s transition will undoubtedly be the most poignant. He’s having to relearn the most basic skills, like how to eat with a fork and how to work his new iPhone. Even a recent trip to the movie theater took some getting used to. “Being in a dark room and having people sit behind me and not expecting them to stab or hit me in the back of the head is really nice,” says Echols, who now wears glasses to correct the vision he lost after years in a cramped cell. “There are so many things he needs to relearn,” says Davis, watching him eat a salad with his hands.

At present, friends have been helping the couple out, providing them with a place to stay and stocking the refrigerator with pizza and chocolate milk (his favorite foods). While Echols says he has no idea what the future holds, he plans to travel to New Zealand in October to spend a month with director Peter Jackson and his wife, who donated untold millions to his cause. But for now, he spends his time wandering the streets, soaking up the sights, and visiting doctors and dentists. One recent afternoon Echols seemed almost giddy, peering into shop windows and watching passersby on the streets. Seeing all that he has missed, is he angry? “If I sat around and dwelled on it, I would be. But I’m not,” he says, explaining anger would be too stressful. “Then I wouldn’t be able to enjoy all of this.”

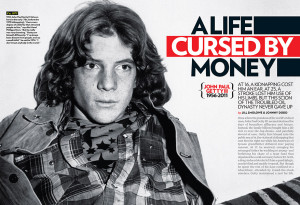

“I promised I’d never give up”

Shortly after Jessie Misskelley’s arrest in 1993, his father pulled a tarp over Jessie’s old Chevy truck and left it parked in the yard. Misskelley insists that when his life finally settles down, the first thing he wants to do is get it running again. “I’m gonna fix it,” says Misskelley, who hopes to one day become an auto mechanic. The former lifer insists that realizing so many people were following the case made all the difference. “Every day I told myself, ‘That’s something to live for,'” he recalls. ” ‘Don’t let them down.'” His biggest challenge these days? “I wake up every night with my back hurting,” Misskelley says with a laugh. “I’m just not used to sleeping on a soft bed.”

“I knew one day we’d be free”

These days Jason Baldwin has only one request of his friends. “I’ve been going around telling people not to pinch me in case this is all a dream,” he says. Since being set free, Baldwin, who is staying at a friend’s house, has been working in construction, in between dentist and doctor appointments. “I lost track of how many times I was attacked in prison,” he says, adding that a day never goes by when he doesn’t think about the three young victims in the case. “Our lives will always be linked together.” This month he hopes to begin taking college courses. After that, law school. “I want to help guys who are in a situation similar to the one we found ourselves in.”

Free, but Still Felons

The three men were able to walk out of prison after agreeing to a complicated legal maneuver called an Alford plea that allowed them to maintain their innocence while acknowledging that prosecutors had enough evidence to convict them. “What the defendants are saying is, ‘I think the prosecution has the evidence against me, but I didn’t do it,'” says Loyola Law School professor Laurie Levenson. Under the agreement, defendants get their freedom, but they are unable to sue the authorities for false arrest, and prosecutors get to say the case is solved. Indeed, police have never identified another suspect in the case, and though Gov. Mike Beebe has the power to pardon the West Memphis Three, he has already said that he will not exonerate them unless new evidence is revealed. “Guilty pleas are supposed to resolve things,” says Levenson. “Alford pleas resolve things legally but leave a huge question mark in the air about what really happened.”